Molecular spintronic action confirmed in nanostructure

"I am Kai, last of the Brunnen-G. Millennia ago, the Brunnen-G led humanity to victory in the war against the insect civilization. The Timeprophet predicted that I would be the one to destroy the divine order in the league of the 20.000 planets. Someday that will happen, but not today. Cause' today is my day of death. The day our story begins." - LEXX

| Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have made the first confirmed "spintronic" device incorporating organic molecules, |

a potentially superior approach for innovative electronics that rely on the spin, and associated magnetic orientation, of electrons. The physicists created a nanoscale test structure to obtain clear evidence of the presence and action of specific molecules and magnetic switching behavior.

Whereas conventional electronic devices depend on the movement of electrons and their charge, spintronics works with changes in magnetic orientation caused by changes in electron spin (imagine electrons as tiny bar magnets whose poles are rotated up and down). Already used in read-heads for computer hard disks, spintronics can offer more desirable properties--higher speeds, smaller size--than conventional electronics. Spintronic devices usually are made of inorganic materials. The use of organic molecules may be preferable, because electron spins can be preserved for longer time periods and distances, and because these molecules can be easily manipulated and self-assembled. However, until now, there has been no experimental confirmation of the presence of molecules in a spintronic structure. The new NIST results are expected to assist in the development of practical molecular spintronic devices.

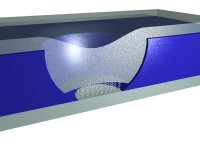

The experiments, described in the October 9 issue of Applied Physics Letters,* used a specially designed nanoscale "pore" in a silicon wafer. A one-molecule-thick layer of self-assembled molecules containing carbon, hydrogen and sulfur was sandwiched in the pore, between nickel and cobalt electrodes. The researchers applied an electric current to the device and measured the voltage levels produced as electrons "tunneled" through the molecules from the cobalt to the nickel electrodes. (Tunneling, observed only at nanometer and atomic dimensions, occurs when electrons exhibit wave-like properties, which permit them to penetrate barriers.)

The pore structure stabilized and confined the test molecules and enabled good molecule-metal contacts, allowing the scientists to measure accurately temperature-dependent behavior in the current and voltage that confirm electron tunneling through the molecular monolayer. Some electrons can lose energy while tunneling, which corresponds to vibration energies unique to the chemical bonds within the molecules. The NIST team used this information to identify and unambiguously confirm that the assembled molecules remain encapsulated in the pore and are playing a role in the device operation. In addition, by varying the magnetic field applied to the device and measuring the electrical resistance, the researchers identified magnetic switching in the electrodes from matching to opposite polarities. ###

This work was supported in part by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

No comments:

Post a Comment