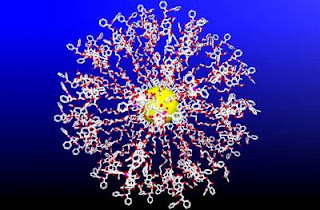

Taxol bristle ball: a wrench in the works for cancer, Dozens of cancer-clogging drug molecules loaded onto tiny gold sphere

HOUSTON, – Rice University chemists have discovered a way to load dozens of molecules of the anti-cancer drug paclitaxel onto tiny gold spheres. The result is a tiny ball, many times smaller than a living cell that literally bristles with the drug.

Paclitaxel, which is sold under the brand name Taxol®, prevents cancer cells from dividing by jamming their inner works.

"Paclitaxel is one of the most effective anti-cancer drugs, and many researchers are exploring how to deliver much more of the drug directly to cancer cells," said lead researcher Eugene Zubarev, the Norman Hackerman-Welch Young Investigator and assistant professor of chemistry at Rice. "We looked for an approach that would clear the major hurdles people have encountered -- solubility, drug efficacy, bioavailability and uniform dispersion -- and our initial results look very promising."

The research is available online and will appear in the Sept. 19 issue of the Journal of the American Chemical Society (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, vol. 129, pgs.11653-11661).

First isolated from the bark of the yew tree in 1967, paclitaxel is one of the most widely prescribed chemotherapy drugs in use today. The drug is used to treat breast, ovarian and other cancers.

Paclitaxel works by attaching itself to structural supports called microtubules, which form the framework inside living cells. In order to divide, cells must break down their internal framework, and paclitaxel stops this process by locking the support into place.

Since cancer cells divide more rapidly than healthy cells, paclitaxel is very effective at slowing the growth of tumors in some patients. However, one problem with using paclitaxel as a general inhibitor of cell division is that it works on all cells, including healthy cells that tend to divide rapidly. This is why patients undergoing chemotherapy sometimes suffer side effects like hair loss and suppressed immune function.

"Ideally, we'd like to deliver more of the drug directly to the cancer cells and reduce the side effects of chemotherapy," Zubarev said. "In addition, we'd like to improve the effectiveness of the drug, perhaps by increasing its ability to stay bound to microtubules within the cell."

Zubarev's new delivery system centers on a tiny ball of gold that's barely wider than a strand of DNA. Finding a chemical process to attach a uniform number of paclitaxel molecules to the ball -- without chemically altering the drugs -- was not easy. Only a specific region of the drug binds with microtubules. This region of the drugs fits neatly into the cell's support structure, like a chemical "key" fitting into a lock. Zubarev and graduate student Jacob Gibson knew they had to find a way to make sure the drug's key was located on the face of each bristle.

Zubarev and Gibson first designed a chemical "wrapper" to shroud the key, protecting it from the chemical reactions they needed to perform to create the ball. Using the wrapped version of the drug, they undertook a series of reactions to attach the drug to linker molecules that were, in turn, attached to the ball. In the final step of the reaction, they dissolved the wrapper, restoring the key.

"We are already working on follow-up studies to determine the potency of the paclitaxel-loaded nanoparticles," Zubarev said. "Since each ball is loaded with a uniform number of drug molecules, we expect it will be relatively easy to compare the effectiveness of the nanoparticles with the effectiveness of generally administered paclitaxel." ###

Research co-authors include Rice graduate student Bishnu Khanal. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Welch Foundation.

Contact: Jade Boyd jadeboyd@rice.edu 713-348-6778 Rice University